The morning light touched Central Park softly that day — unaware of what history would take before nightfall. December 8, 1980. A quiet Monday in New York City. The kind of day that begins like any other and ends by dividing time itself into “before” and “after.”

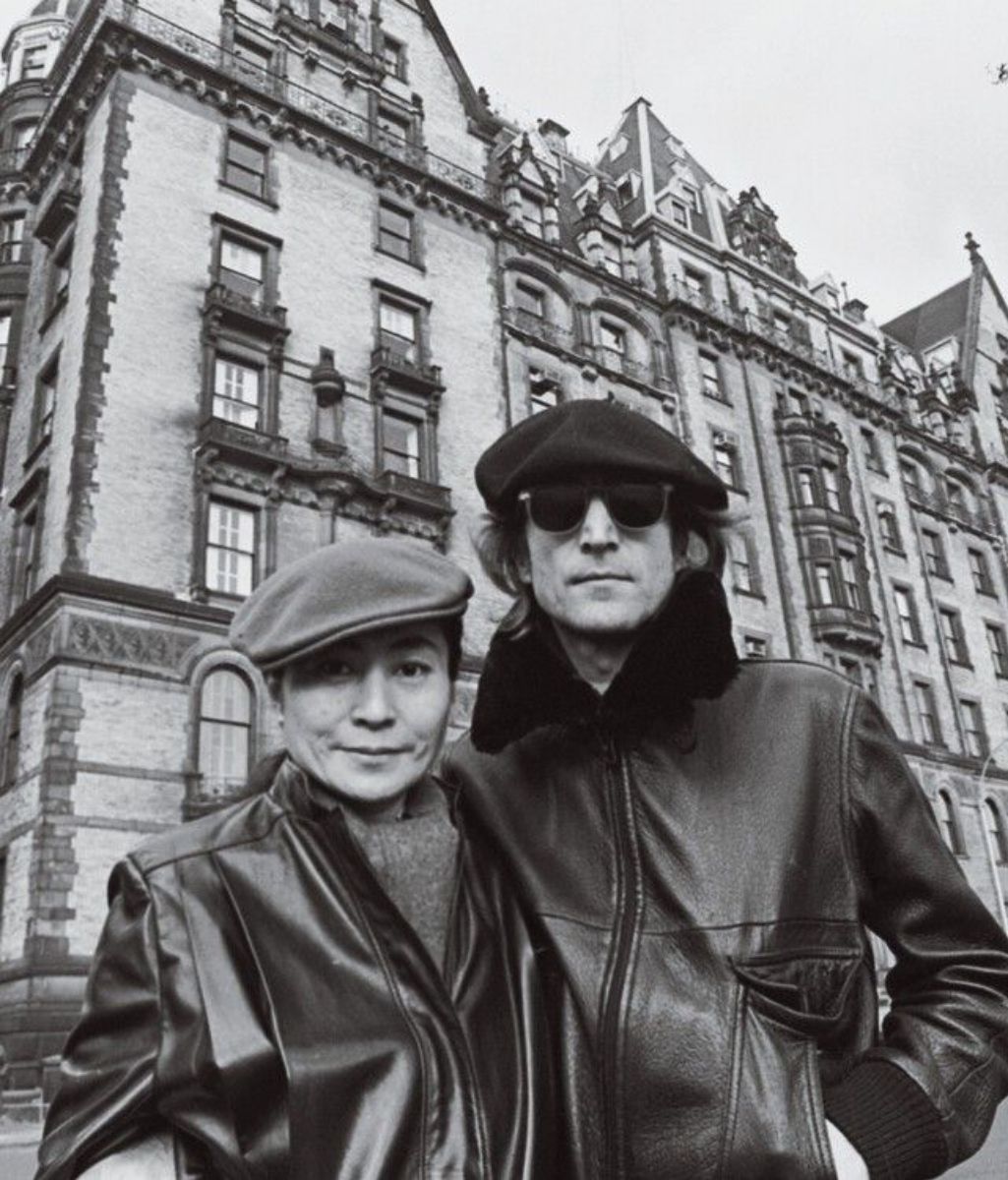

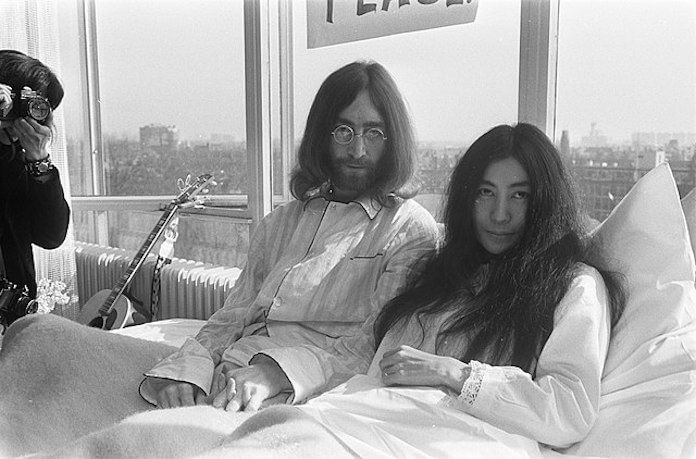

John Lennon, forty years old, woke early inside the Dakota building, the Gothic landmark that had become both sanctuary and stage. He slipped into his black kimono, poured himself tea, and sat near the window as the city stirred to life below. His voice was alive again. After five years away from the public eye, Lennon had returned to music with Double Fantasy, an album that sounded less like a comeback and more like rebirth. It was tender, domestic, hopeful — the work of a man who had rediscovered peace through art, love, and fatherhood.

Beside him, Yoko Ono prepared for another full day of recording and photography. They were riding a wave of creativity, laughing, working, and planning what came next. Few knew how deeply content John felt in those final weeks — “at peace,” as he told friends, “finally where I belong.”

Meanwhile, across the city, another man was moving in the shadows. Mark David Chapman — a troubled drifter from Hawaii — checked his pockets: a copy of Double Fantasy, a pen, and a revolver. He had flown to New York days earlier, drawn by obsession and delusion. For hours he lingered outside the Dakota, blending into the hum of tourists and fans waiting for an autograph.

By afternoon, fate began its slow convergence. Lennon and Yoko left for the studio. Photographers caught them smiling together in the car, unaware that they were documenting their last ride. That evening, as they returned home, Chapman stepped forward from the darkness.

💬 “Is that what you want?” John asked softly as he signed Double Fantasy for him. The words were casual, polite — but eerily prescient. Chapman said nothing. The question hung in the cold air, unanswered.

Hours later, as John and Yoko stepped out of their limousine and approached the Dakota’s archway, five gunshots shattered the stillness. The sound echoed through the Upper West Side like thunder rolling over stone. Lennon collapsed, his body falling toward the doorway of the home he loved.

Paramedics rushed him to Roosevelt Hospital. The sirens that cut through Manhattan that night were unlike any others — urgent, hollow, almost sacred. In the emergency room, doctors fought to save him, but the wounds were too great. A physician later whispered the words no one was ready to hear: “He’s gone.”

Outside, thousands gathered in disbelief. The air was filled with weeping, with singing, with silence. Candlelight flickered in the windows of the Dakota as the city that had given him freedom now carried his final echoes.

Yoko Ono, steadfast and composed, would later turn grief into guardianship — of his art, his message, and the idea that love, even in loss, can still heal.

And though decades have passed, that night has never fully ended. Each time Imagine plays, each time a new voice rediscovers All You Need Is Love, the world is reminded of the truth Lennon left behind: that even when the body fails, the song does not.

Because John Lennon’s music never learned how to die.