There are moments in history when the future reveals itself not through grand speeches or dramatic events, but through something far quieter — a glance, a breath, a shutter click.

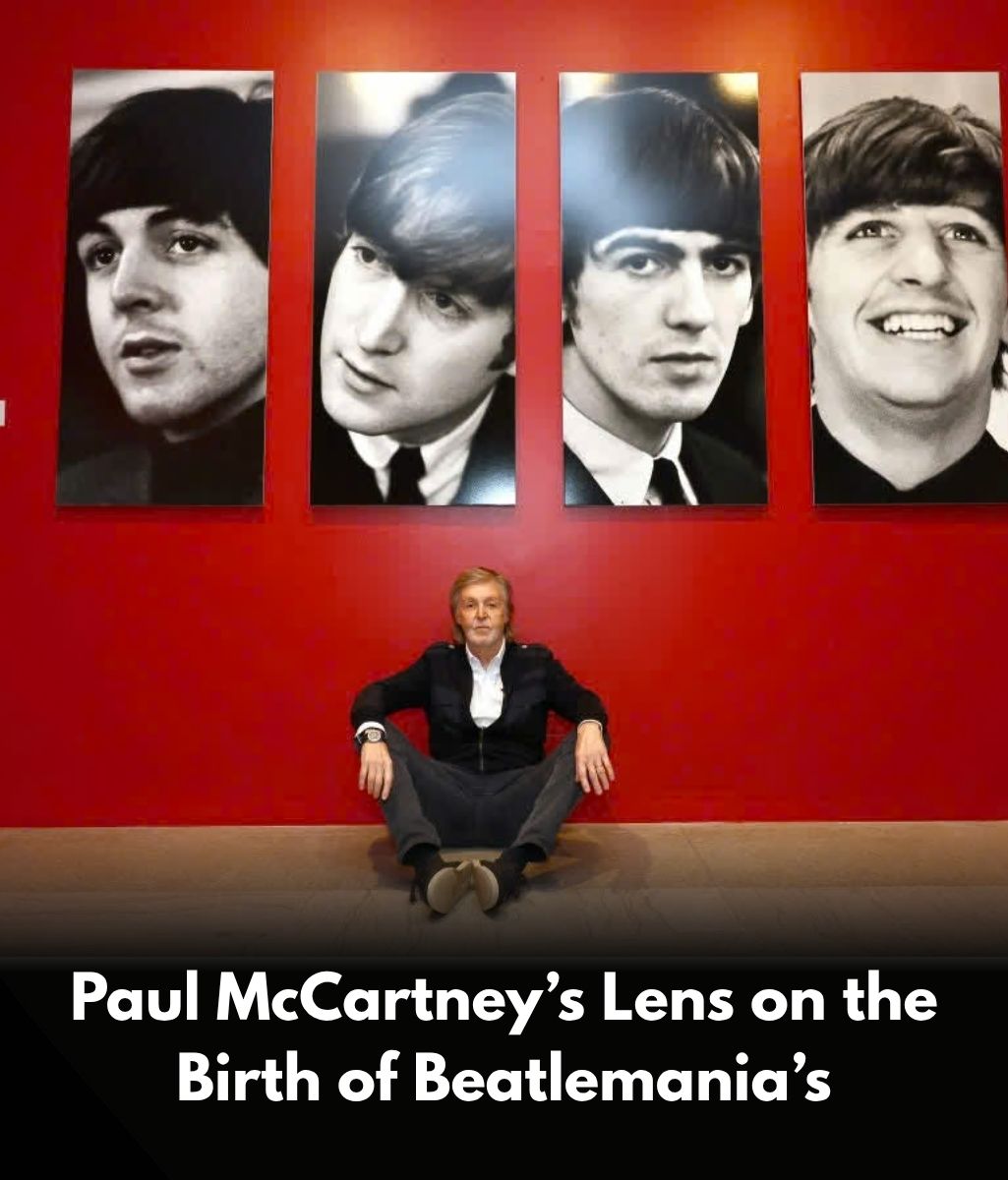

That is the feeling that settles over visitors the moment they step into Paul McCartney Photographs 1963–64: Eyes of the Storm, now on display at the Frist Art Museum. The lights soften, the room stills, and suddenly the viewer is pulled back into the earliest, most fragile days of Beatlemania, seen not from a reporter’s flashbulb or a newsreel camera, but from McCartney’s own hands.

Nearly 300 photographs line the walls, drawn from McCartney’s personal archive and preserved with a tenderness that feels almost private. These are images untouched by the weight of the decades that followed, untouched by the fame that would soon become impossible to outrun. Instead, the photographs pulse with the heartbeat of 1963 and 1964 — a time when four young musicians from Liverpool were still unsure whether the world would embrace them, or even notice at all.

![]()

The journey begins on the streets of Paris. The boulevards blur slightly, not from haste but from movement — the kind of quiet energy that follows any rising group preparing for its first leap into the unknown. Hotel windows glow with a kind of innocence, capturing nights filled with rehearsals, laughter, and the collective understanding that something extraordinary might be stirring just beyond the horizon. The images then move effortlessly across the Atlantic, placing visitors in the thick of New York’s winter air, where the promise of a new world awaited.

Every frame feels alive. The rhythm is swift. The atmosphere is electric yet unforced. There is no attempt to pose or polish. These are moments caught in the in-between — moments too real for publicity and too sincere for performance.

💬 “These weren’t for the press… they were just for Paul,” curator Rosie Broadley says quietly, standing among the candid expressions and unguarded glances that now draw thousands of eyes.

In one photograph, Lennon’s glasses are simply his own — not yet symbols of global identity, not yet relics or emblems, just part of a young man finding his place in a world expanding faster than anyone could comprehend. In another, George Harrison appears barely twenty, studying a future that had not yet been written for him. His posture carries both uncertainty and curiosity, a reminder that fame is not something learned overnight; it is something encountered.

Fans appear in several frames as well — leaning forward with small cameras, unaware that they were capturing moments from a turning point in cultural history. Their presence softens the distance between the viewer and the past, reminding us that Beatlemania was not merely a phenomenon; it was a conversation between four musicians and a world ready to listen.

And through it all, McCartney’s lens remains calm, patient, and observant. It reveals not the polished narrative of legend, but the honest, unguarded truth of beginnings.

By the end of the exhibit, one realization becomes impossible to ignore:

Revolutions do not always begin with noise.

Sometimes they begin softly — honestly — frame by frame.