Some revolutions announce themselves with noise, but others begin in small rooms where tape reels spin, pencils tap against music stands, and ideas collide faster than anyone can write them down.

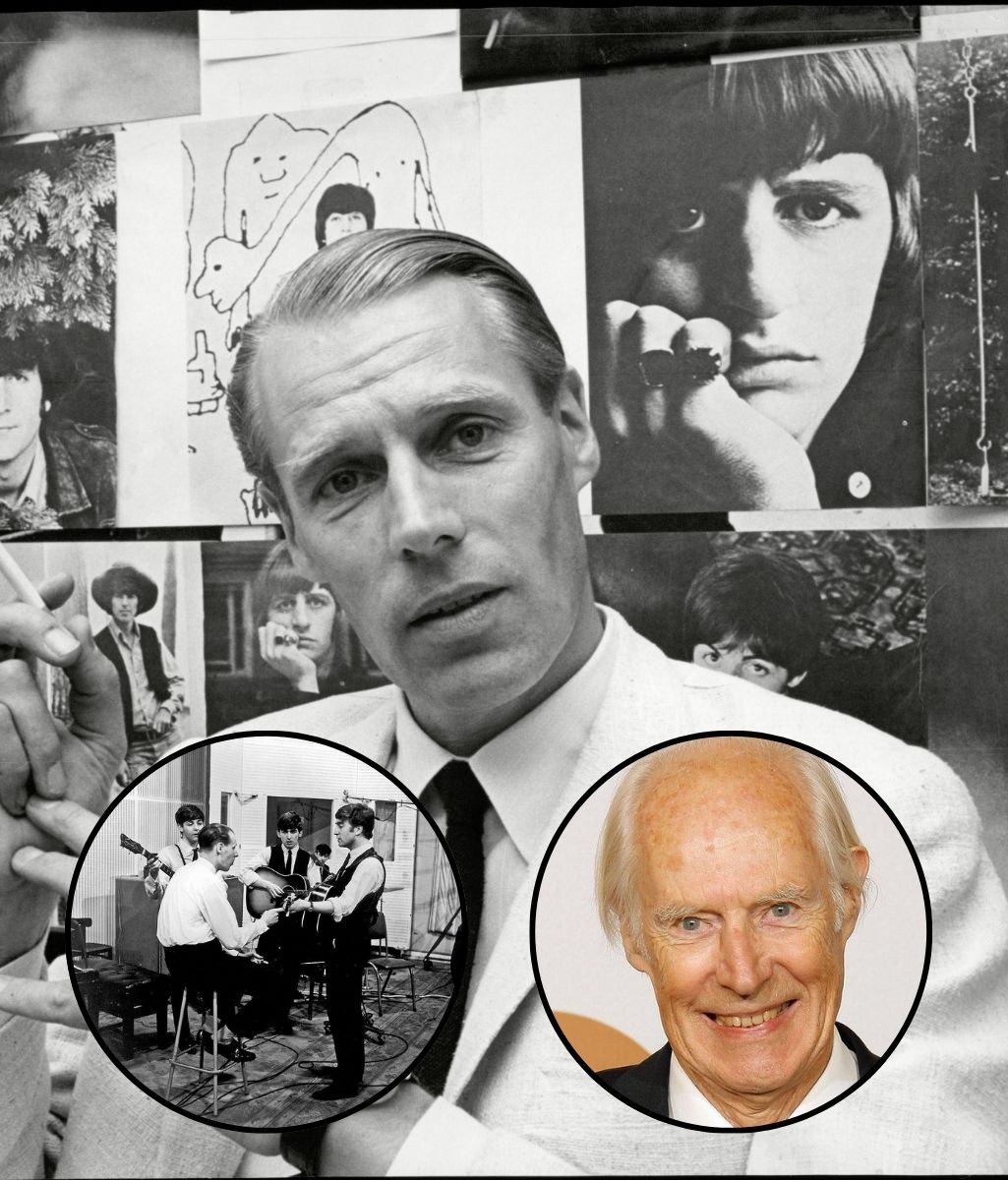

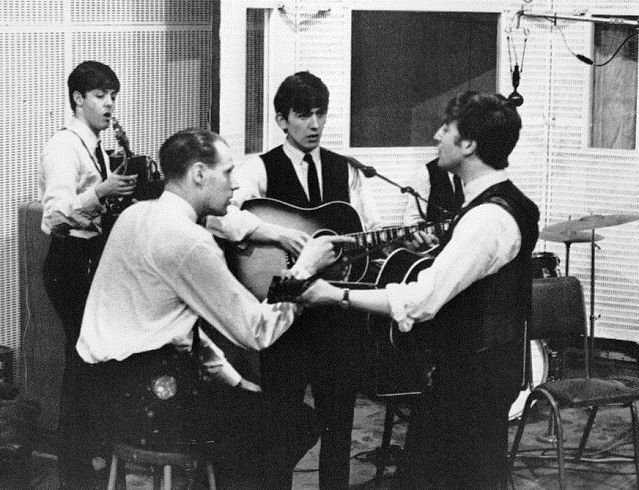

That was the world George Martin found himself in during the mid-1960s, standing inside EMI’s Studio Two and watching four young musicians from Liverpool dismantle everything the world thought pop music was supposed to be. What he witnessed was not just creativity — it was prophecy. And years later, Martin admitted there were moments when he realized The Beatles were not simply ahead of their time. They were building the time the rest of the world would eventually live in.

Martin often spoke with warmth about the group, but when he looked back on their boldest experiments, his words carried something deeper: awe.

💬 “This wasn’t pop anymore — this was tomorrow’s music,” he once said, still astonished by their willingness to push every boundary.

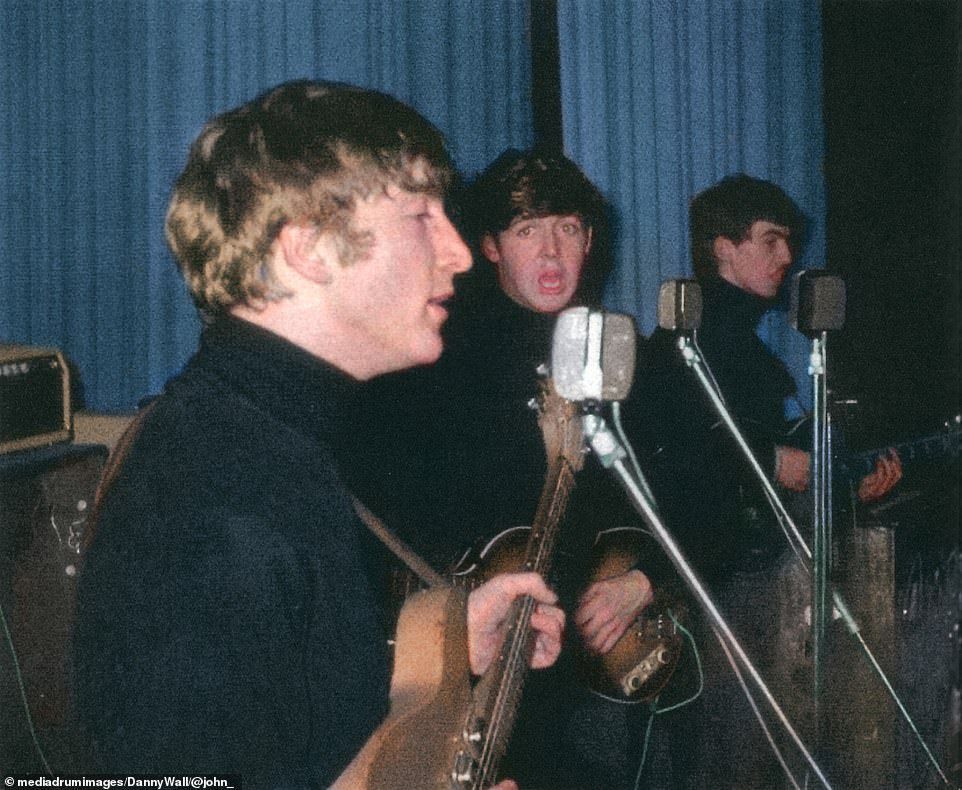

The turning point came long before critics understood what was happening. Inside those walls, the group began insisting on ideas that should not have worked: vocals played backward, tape loops layered like a mosaic, orchestras instructed to climb in controlled chaos toward a note that did not exist, microphones placed in unusual corners, drums captured in strange new ways, and harmonies built with the sweep of cinema rather than the simplicity of radio singles. They were not following trends. They were inventing possibilities.

Among the songs that Martin believed were decades ahead, a pattern emerged — a roadmap pointing toward entire genres that had not yet been named. “Rain” introduced reversed tapes and airy vocal textures that prefigured psychedelia. “Tomorrow Never Knows” created a world of loops, drones, and rhythmic fragments that electronic musicians would not fully explore until the 1980s and 1990s. “Eleanor Rigby” transformed storytelling through a stark string arrangement that abandoned guitars entirely, bringing orchestral chamber writing into the heart of rock music. And “A Day in the Life” blended avant-garde orchestration with intimate lyricism, building a soundscape that felt less like a song and more like an emotional panorama.

To George Martin, these tracks were not steps forward; they were leaps. In them, he heard the seeds of sampling long before sampling existed, the genesis of ambient music before anyone used the term, the foundation of progressive rock before the genre formed its identity, and a level of emotional depth that would redefine what “popular music” meant for generations.

He also recognized their fearlessness. During sessions, the group asked questions no one else in pop music dared to ask:

What if a guitar sounded like a voice?

What if a voice sounded like a machine?

What if a studio wasn’t a room — but an instrument?

And Martin, with his classical training and open mind, helped translate those questions into reality. The partnership between producer and band became the quiet engine behind a new era of sound.

Looking back, Martin often noted that other artists created hits, but The Beatles created influence. Their experimental recordings shaped the vocabulary of rock, electronic music, hip-hop production, film scoring, and even modern digital composition. Effects that are now standard — artificial double-tracking, tape saturation, sound collage, dynamic mixing techniques — began as wild ideas tossed across a room in Abbey Road, executed with scissors, tape loops, and instinct rather than technology.

And so, when George Martin spoke about those ten visionary recordings, he did not describe a band chasing the future. He described a band becoming it. They were architects working without blueprints, building rooms no one had ever entered, leaving doors open for generations to walk through.

More than half a century later, the world now lives inside the musical landscape they sketched. And in those moments preserved on tape, Martin saw something few producers ever witness:

the birth of tomorrow — captured yesterday.