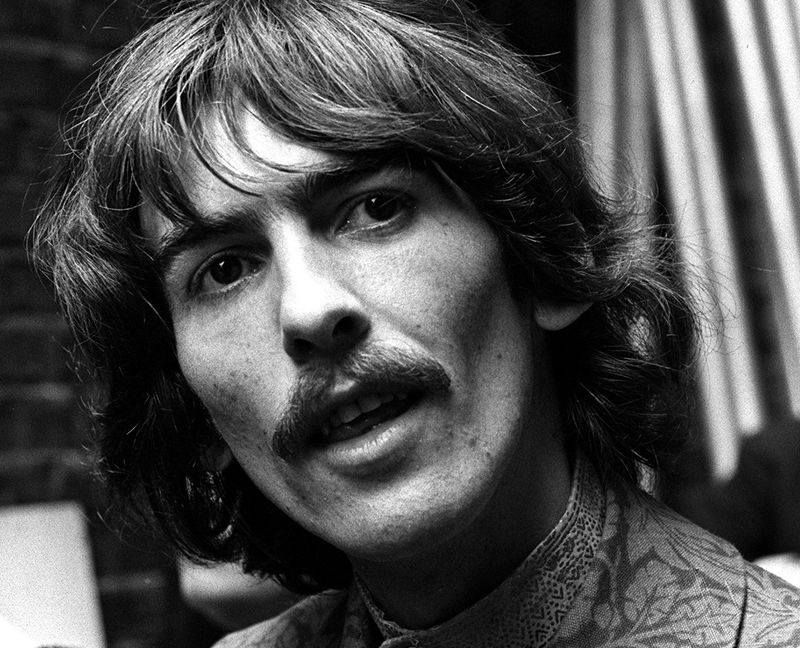

He had always been the shadow behind Lennon and McCartney — the gentle fire glowing just beyond the center of the stage. While the world was transfixed by the brilliant chaos of his bandmates, George Harrison carried within him something subtler, quieter, but no less powerful: a yearning for stillness.

When All Things Must Pass finally arrived in 1970, it felt like a sunrise after years of twilight. It wasn’t merely an album. It was liberation. A man who had spent years standing in the back had stepped into the light — and the world, for once, truly listened.

The music was majestic and immense, a flood of songs that had waited too long to be heard. “My Sweet Lord,” “Wah-Wah,” “Isn’t It a Pity” — each track shimmered with both devotion and exhaustion, joy and melancholy. But brilliance comes at a cost, and for George, the years that followed that triumph were anything but peaceful. Fame had brought him the world, but it had also brought confusion. Business battles, broken friendships, and personal heartbreak began to shadow his newfound freedom.

💬 “I just wanted peace,” he once whispered in an interview, the words almost dissolving into a sigh. It wasn’t a complaint. It was a confession — from a man who had given the world his light and was now searching for a place to rest in its warmth.

That peace did not come from applause or chart success, nor from the Hollywood chaos that swirled around him in the 1970s. It came, quietly and almost invisibly, from home — from the gardens of Friar Park, the Victorian estate that became both sanctuary and symbol. Behind its gates, George built a world of his own making: mornings filled with tea and laughter, long hours spent in his home studio, and the simple pleasure of being left alone with his guitars and his thoughts.

It was here, in that solitude, that George rediscovered something he had nearly lost — the joy of creation without expectation. Out of this period came 33⅓, released in 1976, and with it, a version of George that felt renewed. Gone was the weary spiritual pilgrim of All Things Must Pass; in his place stood a man lighter, funnier, and quietly content. Songs like “Crackerbox Palace” and “This Song” revealed a playful wit, a willingness to laugh at himself, and a refusal to take the madness of the music industry too seriously.

The album glows with humor, tenderness, and quiet grace. It doesn’t reach for transcendence. It settles into something rarer — happiness. You can hear it in his voice: a gentleness that feels earned, a peace that sounds lived-in. For George Harrison, 33⅓ was more than a comeback. It was a homecoming.

By the time the self-titled George Harrison album arrived in 1979, something within him had shifted. The storm had passed. The bitterness had lifted. What remained was the sound of contentment — of a man who no longer needed to chase the world because he had finally found his place within it.

In the end, George didn’t measure success by applause or headlines. His triumph was quieter: mornings in Friar Park, the laughter of friends, the stillness between notes. He had learned, as few do, that happiness doesn’t roar. It hums. It lingers. And for George Harrison, it sounded like 33⅓ — the gentle rhythm of a soul finally at peace.